The Akai MPC didn't set out to truly revolutionize music.

Roger Linn – the guy who'd already built the LinnDrum, the drum machine you hear all over '80s pop – had watched his company crash after the ambitious but buggy Linn 9000 flopped.

It looked done and dusted before the Japanese electronics company Akai approached him with a proposition. Help us build something that combines sampling and sequencing in one box.

Linn, who hated reading manuals himself, had one goal – make it intuitive enough that you wouldn't need to crack open an instruction book to figure it out.

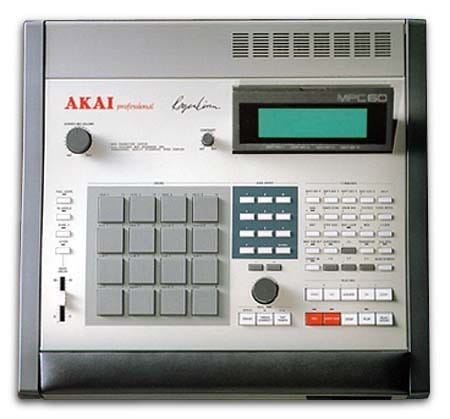

When the MPC60 landed in 1988, it cost $5,000. That's serious money, but compared to the $10,000+ grooveboxes dominating professional studios, it was suddenly within reach for dedicated producers.

More importantly, you didn't need a studio to use it. A bedroom, some records, and ideas proved to be more than enough.

Here’s a brief history of the MPC and how it changed music production forever.

- What Made Those Sixteen Pads Special

- Democratizing Production

- J Dilla – Breaking All the Rules

- DJ Shadow – Redefining Hip-Hop Beats

- The Cultural Takeover

- From MPC60 to MPC Live – The Evolution

- Why The MPC Still Thrives Today

- The Bottom Line

What Made Those Sixteen Pads Special

The MPC offers sixteen big, chunky, velocity-sensitive rubber pads arranged in a 4x4 grid.

There have been loads of versions throughout the years, but the first was the MP60.

Previous samplers and drum machines had tiny buttons and confusing interfaces. The MPC's pads were different – you could bang on them with your fingers like drums, though not requiring percussion skills to use.

Instead of tediously programming beats one note at a time, locked into a rigid grid, you could perform them in a small box – way smaller than an electronic drum kit.

Since the pads are pressure-sensitive, you could tap lightly for ghost notes, which added to the expressive potential.

Linn also built in an adjustable swing – a feature that became absolutely crucial. Swing lets you delay every other 16th note by adjustable amounts. Set it to 50% and you get perfectly even timing.

But adjust it toward 66% and the beats start to shuffle, to breathe, to groove like a human drummer who's slightly behind or ahead of the click.

The MPC combined everything in one box: sampler, sequencer, pads, MIDI, and storage.

Plug in a turntable, sample some drums and loops, arrange them into a beat, save it to disk – all without leaving the box.

Democratizing Production

Before the MPC, professional music production meant expensive studio time or major capital investment in gear.

If you wanted to make sample-based hip-hop in the mid-'80s, you needed access to professional equipment that cost tens of thousands of dollars.

The MPC60's $5,000 price tag was still substantial – about $13,000 in today's money. But it was attainable and came down rapidly after a few years.

Moreover, you didn't need to know music theory or play traditional instruments, and the MPC was approachable in ways that synths and e-drum kits weren't.

You could sample someone else playing piano, chop it up, and rearrange it into something new without knowing anything about chord progressions.

This democratized music production at a time when hip-hop was rapidly breaking through into the mainstream.

J Dilla Breaking All the Rules

The MPC's swing feature proved incredibly impactful. But you could also not quantize at all.

Take James Yancey – J Dilla – who turned quantize off. He'd record basslines slightly behind the beat, drums slightly ahead, creating this drunk, off-kilter feel that became definitive across hip-hop and tons of other sub-genres outside of it.

After Dilla died in 2006 at just 32 years old, his actual MPC3000 was inducted into the Smithsonian's National Museum of African American History and Culture.

DJ Shadow Redefining Hip-Hop Beats

In 1996, DJ Shadow released Endtroducing, an instrumental hip-hop album created entirely from samples.

Shadow spent two years making it with minimal gear, including an Akai MPC60 sampler, a Technics SL-1200 turntable, and an Alesis ADAT tape recorder. He'd spend hours at Rare Records in Sacramento, digging through forgotten vinyl, then take his finds home to chop and rebuild.

Endtroducing eventually earned a Guinness World Record as the first album created entirely from samples. But the true significance was proving that sampling could be a complete compositional tool, capable of creating complex, emotionally resonant music that worked as full albums.

The Cultural Takeover

By the late '90s and early 2000s, the MPC had become synonymous with hip-hop production itself.

The list of influential producers who made the MPC central to their workflow reads like a hip-hop hall of fame:

- Dr. Dre – Used multiple MPC3000s on The Chronic and 2001

- DJ Premier – Gang Starr's signature boom-bap sound came largely from his MPC work

- Pete Rock – Built his reputation on MPC-driven beats sampling jazz and soul

- Q-Tip – Used the MPC to create A Tribe Called Quest's jazz-rap fusion

- Kanye West – Built much of The College Dropout using an MPC2000

- Flying Lotus – Brought the MPC aesthetic into experimental electronic music

That 4x4 pad grid became so iconic that every manufacturer copied it. Native Instruments built Maschine around the concept. Ableton created Push with the same layout. Even cheap MIDI controllers copied the design.

The visual language became universal. See a producer with their fingers flying across sixteen pads and you instantly know what's happening.

The MPC really is burned into the culture. There will always be some prestige attached to using one.

From MPC60 to MPC Live

The MPC60 wasn't perfect. Far from it. But it worked well enough that Akai kept refining the concept for decades.

MPC60 (1988)

The original. 12-bit sampling at 40kHz, 13 seconds of total sample time, 16 voices of polyphony.

The screen was tiny, the interface basic, but it did what it needed to do.

MPC3000 (1994)

This is the one everyone remembers. The last MPC that Linn worked on before parting ways with Akai.

It featured 16-bit sampling at 44.1kHz, up to 32MB of RAM, and 32 voices. The MPC3000 is the model sitting in the Smithsonian – Dilla's unit specifically.

These go for $3,000-$5,000 used now, sometimes more if they're in good condition. Producers swear the 3000 has a specific warmth and punch that later models don't quite capture.

MPC2000/2000XL (1997/1999)

Akai made these without Linn's involvement. The 2000 was more affordable and compact, which helped it reach even more producers. The 2000XL added time-stretching, resampling, and better effects.

This became the workhorse MPC. Not as expensive as the 3000, more features than the 60, reliable as hell. If you see an MPC in a mid-2000s hip-hop video, it's probably a 2000XL.

MPC4000 (2002)

The kitchen sink model. 24-bit sampling, hard disk recording, CD burner, tons of effects, massive screen. Akai tried to make it a complete production studio.

It flopped because it was too expensive, too complicated, and tried to do too much.

MPC1000/2500/5000 (2003-2008)

Akai released a bunch of models, trying different price points and feature sets.

The MPC1000 became popular as a portable option. The 2500 was basically an updated 2000XL. The 5000 had an internal synth.

None of them quite captured the magic of the 3000 or the ubiquity of the 2000XL, but they kept the line going.

MPC Renaissance/Studio (2012-2013)

Akai tried something different – MPCs that required a computer to run. They were essentially MIDI controllers for MPC software.

Producers hated it. The whole point of an MPC was that it was standalone, self-contained. Making it dependent on a computer defeated the purpose.

MPC Live/X/One (2017-Present)

Akai finally figured it out again. These are standalone units that don't need a computer, but they run modern software with touchscreens and can load VST plugins.

The MPC Live is battery-powered and portable. The MPC X is the flagship with a big screen and more I/O. The MPC One is the budget option. All three run the same software, so you get the classic MPC workflow plus modern features.

These are selling well because they bridge both worlds – you can work standalone like the classics, or connect to a computer if you want. The workflow feels familiar to anyone who used an older MPC, but you're not stuck with 1990s limitations.

Why The MPC Still Thrives Today

The MPC came out in 1988. Nearly 40 years later, producers still use them for specific production techniques that are harder to achieve any other way.

Here’s why:

Finger Drumming and Live Playing

Hit record, play your pattern with your fingers, capture the performance. It’s easy. And you really don’t need to be a drummer.

This technique is huge for:

- Creating patterns with natural swing and groove

- Adding fills and variations on the fly

- Building beats that feel less rigid and programmed

- Performing live without just pressing play

Chopping Samples to Pads

The classic MPC workflow: sample a break or loop, chop it into pieces, and assign each piece to a different pad. Now you can rearrange the sample by hitting pads in different orders.

Take a four-bar drum break, chop it into 8 or 16 pieces, and spread them across the pads. Now you can play those pieces in any order, creating entirely new patterns from the original break. This is how producers like J Dilla and DJ Premier built their signature sounds.

Pattern-Based Arrangement

MPCs work in patterns – short loops you create and then chain together. Make an 8-bar drum pattern, a 4-bar bass pattern, and a 16-bar melody pattern. Chain them together to build full arrangements.

This keeps you thinking in sections rather than getting lost in linear timeline editing. You're building blocks that you can rearrange, which makes it easier to try different song structures.

The Bottom Line

Turns out, making gear intuitive and playable was more important than making it feature-packed. The MPC succeeded because it got out of the way and let producers focus on music instead of fighting with technology.

Nearly 40 years later, that basic idea still holds up. Pads you can hit, patterns you can chain, samples you can chop – it's a workflow that makes sense whether you learned it in 1990 or last week.

The MPC isn't going anywhere. And judging by how many producers still swear by them, that's probably a good thing.

Need sounds to load onto those pads? Sample Focus has thousands of drum breaks, loops, and one-shots ready for chopping. Browse the collection and start building.

Comments